|

<<

Back to The Sand Paper Index Page

|

|

Traditional Iipay Pottery

By Jeannie Beck

This article was originally published in The Sand Paper, the membership

newsletter of the

Anza-Borrego Desert Natural History Association |

|

|

|

|

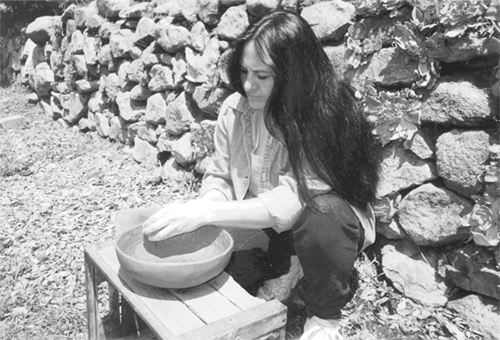

Heidi Osuna is carrying on the family tradition of aaskay, as it was called by her ancestors, the Northern Diegueno (or Iipay, as they call themselves). Aaskay translates to “mud work,” but today we call it pottery or art.

Heidi climbs a trail up Volcan Mountain, which is situated behind her house on the Santa Ysabel

Reservation (southwest of Borrego Springs), to dig the red clay and carry

it home in a bucket. She uses the traditional tools of a rock and wooden

paddle to smooth the coils from the clay, the same way her father showed

her and his grandmother showed him before. After the clay has taken shape

and dried, Heidi fires the pottery in a pit she has dug outside her

kitchen door. Each piece has a unique shape because it is handmade, and a

unique design because each firing creates a fresh

interplay of fire and smoke, producing endless variations of black

shapes on the red clay. |

In the family tradition of aaskay, or mud

work, Heidi Osuna uses a traditional wood paddle to smooth and shape

a red clay bowl. This method of creating pottery is a

generations-old tradition of the Northern Diegueno or Iipay people. |

|

|

|

|

The Iipay were likely the first snowbirds of the Borrego Desert area, customarily making extended trips to the Salton Sea to collect salt. Knowing this, it’s no surprise that some ancient pottery displayed in regional museums bears a striking resemblance to Heidi’s. Her pottery is made in the same manner as the aaskay

of ancient days, without the modern contrivances of wheels, kilns, or

additives of any kind. Occasionally, she applies a finish of pine

pitch, which she also gathers from nearby pines and then melts onto

the warm ollas. Heidi’s father, known as Yellow Sky, single-handedly

revived this ancient tradition years ago, much to the delight of

museums and galleries across the nation, and now her work is receiving

as much attention. Shy, like her father, Heidi also repeatedly

declines offers to lecture or go on the circuit to |

|

promote her work. It doesn’t seem to be much of a drawback however, as

she is now the only one of her kind creating it. She is sought out by

those who know the value of her work, and word of mouth suffices to

bring in more requests than she can keep up with. People who see the aaskay often want to touch, hold and smell it. Its

beauty is more than visual. The culture it springs from seems nearly

as old as the clay itself. We are grateful that it has found its way

through countless tribulations of generations, not as fragments found

in the sand from a forgotten people, but whole and sparkling anew

through Heidi’s able hands. |

|

Yellow Sky, Heidi

Osuna’s father, puts finishing touches on a bowl about to be placed in

the narrow firing pit used by the aaskay methods. Because of the way

the firing pit has been made, smoke from the fire will mark the bowl. |

|

|

© Anza-Borrego Desert Natural

History Association, from “The Sand Paper” newsletter. |

|

|

|

|

|

|